In the age of User Experience, what is branding? Is a brand just a logo, or is it more than that? Does the word brand even mean anything anymore?

To answer these questions, let's take a quick look at the history of branding.

The Ancient Art of Branding

We often think of branding as a recent phenomenon, but it's not.

No animals were harmed in the Photoshopping of this image.

The original brand was a reference to the physical branding of cattle and livestock, dating back to 2,000 BC.

Since then, anything and everything has been branded. Bread makers, goldsmiths and silversmiths have placed their brand marks on goods in England as early as the 1200s. Printers used watermarks to brand their paper. Even criminals and slaves have been branded, rather cruelly.

Early companies that sold medicine and tobacco began to brand their products in the early 1800s. Proctor and Gamble, and other large consumer goods businesses, followed suit in the same century.

Branding, at least as we once knew it, exploded during the industrial revolution. By this time, brands were in their infancy. A brand was really just a logo, and a way to introduce mass-produced stuff to the world.

After World War II, consumerism stepped up a notch with heightened consumer choice increasing the need for product differentiation. Branding was no longer just a logo. The brand became the communication of a product's features and benefits, and its emotional connection with consumers. The physical packaging of a product became part of the brand, too.

Branding was a cornerstone of the Advertising and Marketing arena, all the way up to the 90s. The Brand Manager, usually a marketing type, was the chief steward of the brand. Brands advertised to consumers, using really big advertising budgets. Consumers would buy said brands. They called it the TV-Industrial complex.

Until this point, a brand was essentially a one-way dialogue from producer to consumer. Then the Internet turned up. And things changed.

What does branding mean today?

In a post cluetrain world, marketers were forced, rather abruptly, to change. Marketing became two-way, and brands were forced to deal with the brave new world of the Internet. The old way of marketing felt a bit dirty, so the marketing profession went through an identity crisis.

As a result, there's still quite a lot of some confusion as to what branding actually means in the Tenties.

There isn't one standard definition of branding anymore. Here are a couple:

Our brand will only ever be the memory of the experience our people had when interacting with us.

Brand is a stand-in, a euphemism, a shortcut for a whole bunch of expectations, worldview connections, experiences, and promises that a product or service makes, and these allow us to work our way through a world that has thirty thousand brands that we have to make decisions about every day.

In both these definitions, the brand is certainly no longer just about the visual cues. It's every cue that your customer has about you. The one word that these definitions both have in common—the experience.

Ask many UXers, and they'd probably tell you that they work on experiences, not brands. They'd say that branding is what's done by branding agencies—the logo, typefaces and a style guide.

Many businesses still assume, incorrectly, that a new brand identity can fix their woes. Slap on a new logo with a fancy new font and colour scheme and your customers will forget every single bad interaction they've had with your organisation. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple.

Organisations need to fix the experience that people are having with the brand.

As experience designers, we understand the need to improve every touchpoint, across every channel. It's not until we're satisfied with each improvement that we should we think about rolling out a new logo, or brand identity.

You also hear a lot less about the traditional brand elements of Price, Product, Place and Promotion. Instead, there's talk of Impression, Interaction, Responsiveness and Resilience:

- Impression—what does the brand say to me about me?

- Interaction—does the brand do what it promises to do?

- Responsiveness—does the brand respond to my needs?

- Resilience—does this brand cares about our future?

[Source: The four elements of a great brand experience]

But is this branding? Or is it experience design?

Truth is, it's a bit of both.

The online experience

When we design an online experience, we need to consider total impression, made up of every single online touchpoint:

- The user interface, defined by the UI Design (and front-end code)

- The colours, images, typography, and other visual elements

- The usability, across all devices and platforms

- The interaction design, transitions and animation

- The content strategy touchpoints (email notifications, social media prescence)

- The tone of voice and personality evident in copy, customer support and error messaging

- The performance. Slow, error prone websites can really an online brand experience

- The micro interactions, or moments of delight

The delivery of great online brands may feel like a happy accident. But more often that not, it's the hard efforts of a strong UX team.

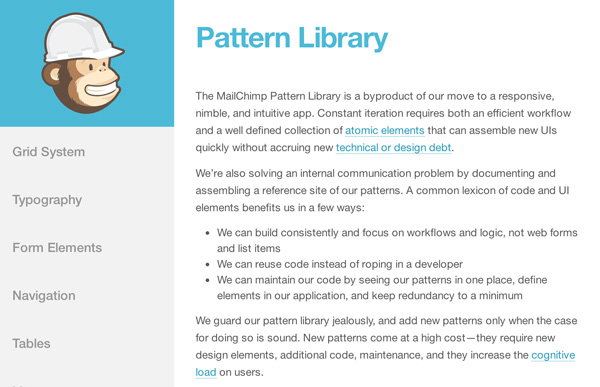

A great example of this is Mailchimp. Their delightful online experience has been well orchestrated by their award-winning UX team. Using design patterns, style guides and voice and tone guidelines, Mailchimp is an online brand done well.

Marketers are still involved in the process but in most cases; it's the UX team that best influences the online experience. This, in turn, influences the brand experience.

The multi-channel experience

So far, we've talked mostly about online. Things get a little more complicated when you consider that most brands aren't exclusively on the web.

Almost every product or service exists both online and offline, with a combination of digital and offline touch points. Most brands are cross-channel in some way.

We've seen a rise in Service Design and Customer Experience (CX) to deal with this. User-centred service design is still a new area, but we all understand the need to identify, research, and evaluate the customer and their journey.

UX and CX designers strive to create flawlessly delightful experiences, regardless of the channel. And if done well, the total experience can make you fall in love with a brand.

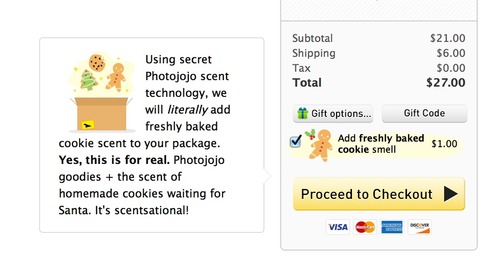

Here's a recent example from Photojojo, an online camera store. It's a simple and fun website, full of personality. Photojojo are often praised for their web experience.

This Christmas, they've added a brilliant little micro-interaction to their service—a cookie scent to their packages. It’s a fun idea that creates a positive brand experience, not only at the online point of purchase, but in the final offline delivery.

Customers love the Photojojo brand, because the experience is so good.

No doubt there's been a UX designer involved along the way.

Brand is just another way to say Experience.

So what does all this mean for branding? And where does it leave the marketing department?

The Brand is alive and well. It's just that we use the term less frequently.

The brand isn't just the logo. The brand is the sum of the entire experience. That’s why branding and experience design are indistinguishable, in many ways.

Like it or not, there's not much difference between UX designers and marketers either. We're both interested in our customers. We're both fascinated about analytics and conversion data. We're both keen to learn, test and iterate to get to the best result.

Whether you're an information architect, a content strategist, a UX or UI designer, a developer, or even a marketer, you're probably passionate about designing the experience, and influencing the brand.

We’re all marketers now.

User experience didn't kill branding. User experience is the branding.